Awhile back I put up a piece about multi-track recording. It included a modern adaptation of a solo cello piece written in about 1715 by Johann Sebastion Bach, probably, of all things, as a practice piece for his students. Having heard the fancy new version, I thought it would be interesting to hear how the original version sounded.

And by “original” I mean original. The cello in this recording was constructed in Bach’s lifetime, only 20 or so years after he finished this composition. It’s over 280 years old.

If you go back and listen to the modern version, you’ll notice that the modern cello sounds very different.

The modern cello emphasizes higher tones or harmonics of the instrument – it sounds “brighter.” This is, in part, because the more modern instrument has metal strings as opposed to the natural gut strings – made from animal sinews – of the older “baroque” cello.

The effect is to make the older instrument sound much less bright, with a much more assertive bass sound. I really prefer the sound of the baroque cello, especially for this kind of music. Hearing the depth of that sound, it’s amazing what these instrument makers were able to achieve 300 years ago with simple hand tools and pieces of wood hauled out of the forest.

Of course, the greatest cello is nothing without an equally great cellist like Ophelie Gaillard. It’s interesting to see her level of concentration. Clearly she is listening to what she is playing, occasionally correcting to obtain the sound she wants. Sometimes we can see her pulling or “bending” the string sideways to raise the pitch if she fingers the note just slightly wrong. Here is a real talent.

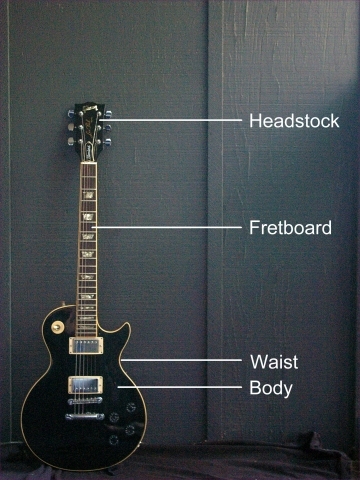

(Bending strings is often done with electric guitars too, but for a different reason. With a reasonably skilled player, the frets on the guitar insure the tone will be right when the note is fingered. Guitar strings are usually bent for dramatic effect rather than to correct the tone as it is on the cello or other stringed instrument without frets. To hear the effect of bending the strings on an electric guitar, checkout my post Wonderful Tonight: Three Guitars, One Song.)

People who see this video are usually surprised to see the cellist, Ophelie Gaillard, holding the instrument with her lower legs – there is no spike or endpin on the bottom. Why is this?

Well, in the baroque period luthiers (the people who make stringed instruments) hadn’t yet invented the metal spike that is a familiar part of modern cellos. In all likelihood this is simply because Home Depot hadn’t been invented yet, either.

Remember, this was well before the industrial revolution, when everything was made by hand, and metals were difficult and expensive to obtain. One did not just run down to Home Depot and buy some files, saws, and chunks of steel. The tools required to work the metal were even more expensive and rare, so musicians simply held the cello as though it were a giant violin, which it very much was. It wasn’t until many years after this cello was made that endpins became common.

One effect of holding and playing the cello without an endpin is that the instrument isn’t as stable. This makes it harder to do that thing where the player wiggles her fingers back and forth, called “vibrato.” Or, put another way, the spike makes it easier for modern players to get carried away with vibrato. Again, if you compare the modern version and this version of the piece, you’ll see that Steven Sharp Nelson uses far more vibrato than does Ophelie Gaillard.

More isn’t necessarily better. Leopold Mozart, father of the more famous Wolfgang Mozart, wrote a best-selling book on violin technique in which he complained about musicians getting carried away with vibrato. He ridicules violinists “who tremble constantly on every note as if they had the permanent fever.”

Wolfgang Mozart once wrote to his father describing vibrato as a natural and beautiful part of music, just as it is in the nature of the human voice. So long as it was used discreetly to emphasize a phrase or note, he was fine with it.

We don’t get to see how this video was recorded, but it seems likely that it too, just like the modern version, is a multi-track recording. There are good reasons for making a multi-track recording even, sometimes especially with, a single instrument.

During a live musical performance, sound bounces around the room, creating reverberation that adds a fullness to the sound. Reverb, as it’s commonly known, is so important to our perception of the sound that it’s very common to add this reverberation electronically to movies scores and electric guitars. Without the reverb electric guitars can have a lifeless sound that doesn’t work with certain types of music.

In any case, if the microphones are placed close to the cello, the reverb will be lost. If the microphone is placed too far away, there will be too much reverb and certain subtle sounds from the instrument may be lost. The way to avoid these problems is to record several tracks at the same time, with microphones in different positions, then mix the tracks to obtain the desired final sound.

Finally, I should probably explain the term “baroque.”

The term came into somewhat common use in the 1800s to describe the music of such composers as Bach and Handel. At the time, critics thought their music was too complex, too ornate, and calling it “baroque” was intended to be an insult.

Today the negative meaning is gone, and the term is simply used to describe the work of Western composers from about 1600 until about 1750, beginning with an Italian composer named Claudio Monteverdi, and ending, roughly, with the German Johann Sebastion Bach.

Copyright 2018 — 2021 by Toni Pfau. All rights reserved.

Contact Toni Pfau at:

503-358-5359

13530 N.W. Cornell Road

Portland, OR 97229

Toni.L.Pfau@gmail.com