What are the differences between Classical, Acoustic, and electric guitars? People ask me. Through the magic of YouTube videos I’ve found a nice way to see and hear the differences.

I searched out three performances of the same song, one performed with an Acoustic guitar, another with a Classical guitar, and another with the song played, as written, on an electric guitar. The song is Eric Clapton’s “Wonderful Tonight.” Three guitars, one song.

But before we look at the videos, it will help to understand the differences if we take a quick look at how the guitar developed over time. Then we can compare how they look, sound, and are played, and the differences will make more sense.

What we now recognize as the “Classical guitar” was essentially fully developed by the famous C.F. Martin & Company by the time of the American Civil War (1861 — 1865), though guitars of the time tended to be quite a bit smaller than they are today.

Guitars were often played in the parlor (the home theater of its day) for entertainment on Sunday evenings, back in the days before cars, radios, TV, movies, or the internet. But professional musicians asked luthiers (the people who make stringed instruments) for instruments that were loud enough to be heard in larger venues.

Luthiers experimented with larger bodies and, eventually, steel strings. Combining the larger bodies and steel strings with different production methods allowed by industrialization brought about, by the 1930s, what we now recognize as a conventional Acoustic guitar.

But professional musicians wanted still more volume. In the 1930s musicians experimented with putting microphones in guitars. They wanted to play with the “Big Bands” of the era and not be drowned out.

Microphones were problematic in light, hollow wooden instruments and have been largely abandoned. In the 1950s guitars with solid wood bodies and specially designed electro-magnetic “pickups” hit the market, and the electric guitar was here to stay.

Each of these changes, to steel strings and larger bodies, to solid wood bodies and electronic pickups, has changed the sound of the guitar and how it is played. Let’s check out the differences.

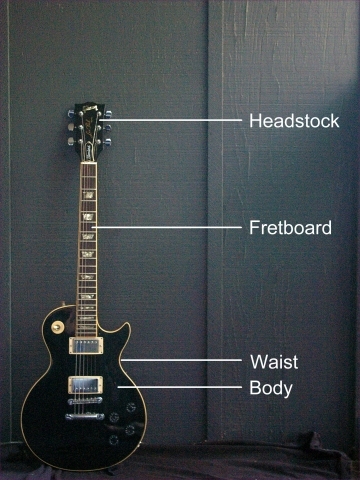

First up, the Acoustic guitar. (Hint: take a close look at the headstock of the Acoustic guitar. Later, we’ll see that it is very different from the headstock on the Classical guitar.)

This is a fairly conventional, though very well made, Acoustic guitar. Plucking the strings gives a strong percussive sound, with a distinct bass and strong clear highs — the sort of sound we would expect from a high-quality guitar of this type.

The neck and headstock are conventional, and the yellowish color of the top of the body tells us that it is spruce, the usual light, strong wood used for guitar tops.

Normally the sides and back of the body are made of mahogany or rosewood. Mahogany and rosewood are dense and hard. They are used because they don’t absorb the vibrations of the strings, helping project the sound out the soundhole in the front of the guitar.

This Acoustic guitar has a large, somewhat squarish body, with a wide waist. This larger body, refered to as a “Dreadnought” body, makes the guitar louder and provides a stronger bass sound.

Not all Acoustic guitars have the large Dreadnought body, but it’s pretty common. It makes a nice-sounding guitar, but it’s usually too big for anybody except adults.

Finally, notice that the player holds the guitar by laying the guitar’s waist over his right leg. Not all Acoustic guitarists do this when seated, but it’s very common.

Now let’s check out the Classical guitar, grandfather of the Acoustic guitar. Again, take a close look at the headstock.

The dead give away on whether we are looking at an Acoustic guitar or a Classical guitar is in the head stock. Where the headstock on the Acoustic guitar is a solid piece of wood, the headstock on the Classical guitar is always distinctly slotted.

The slots are there because the Classical guitar uses a different type of tiny, geared, “tuning machine” to tighten the strings. This is a holdover from when there were no tuning machines, and guitars had tuning pegs the way violins do.

In any case, when we see a guitar with a slotted headstock, we are looking at a classical guitar.

There are other differences.

The neck is distinctly wider and less tapered than on any other type of guitar. This works well ergonomically because of the way the Classical guitar is held and played. The Classical guitarist always plays seated, with the guitar held diagonally across the body, with the left foot upon a small stand and the waist of the guitar laid across the left leg.

The Classical guitar doesn’t have quite the same distinctive percussive sound when strings are plucked, and it doesn’t have the deep base and ringing highs of the Acoustic guitar. There are several factors which contribute to this.

First, a big part of this difference comes from the strings. The Classical guitar uses nylon strings rather than the steel strings for which the Acoustic guitar is designed. The nylon strings simply can’t generate and transmit enough energy to the thin wooden top to produce the deep bass and those ringing highs that steel strings can. (You should never put steel strings on a Classical guitar. Steel strings require much more tension, and putting them on a Classical guitar will damage the guitar.)

Second, the body of the Classical guitar is smaller, which means bass notes can’t be as dominant.

Finally, the reddish wood on the top is cedar, which is very common — though not universal — in Classical guitars (spruce tops are also common). The cedar contributes to the distinct Classical sound.

Now, the electric guitar, played by the man who wrote “Wonderful Tonight”:

The guitar body is quite small because it is a solid piece of wood — hard, dense, heavy wood. It’s hard, dense, and heavy so it doesn’t absorb energy from the strings, which is exactly the opposite of the non-electric (that is, lower-case-“a” acoustic) guitars.

Since the strings can’t transmit vibrational energy to the wood, the strings will ring for a long time after they are plucked. This allows the musician to make all sorts of sounds that are very difficult or impossible to make on any acoustic guitar.

This sustain is what allows, for example, Eric Clapton to bend the strings sideways to vary their pitch, giving the song it’s distinctive little riff. Because the strings on an acoustic guitar can’t sustain that sound, bending the strings to get that effect generally won’t work well, and the player must use a different technique to get the same sort of effect.

The electric guitar neck is quite narrow. Again, this is an ergonomic thing. Electric guitars are generally played in a much more horizontal position than other types of guitars, and wrapping the hand around a wide Classical-style neck would be very difficult.

Electric guitars are not naturally musical sounding the way acoustic guitars are. As with the acoustic guitars, the wood of which the body is constructed makes a significant contribution to how the guitar sounds, but the many harmonics and overtones that give the acoustic guitars their complex melodic sound can’t be captured by conventional electro-magnetic pickups. The result is that there are innumerable electronic devices for changing the sound quality of electric guitars.

One final note: the electric guitar is generally played with a pick. The Acoustic guitar is played with either a pick or, as we saw here, using just the finger tips (“fingerstyle”). The Classical guitar is always played fingerstyle.

I figure that, after our little trip through Guitarland, you know more about guitars than 99 percent of the population. Now you can impress your friends and frustrate your enemies with your seemingly immense knowledge of music!

Copyright 2018 — 2121 by Toni Pfau. All rights reserved.

Contact Toni Pfau at:

503-358-5359

13530 N.W. Cornell Road

Portland, OR 97229

Toni.L.Pfau@gmail.com